And now? Europe at a crossroads

This is the fourth and – for now – final part of a four-part series on China's remarkable transformation. A personal account from a long-time observer.

The uncomfortable question

In the first three parts of this series, I described what I have observed in over twenty years of experience in China: from the VW-dominated streetscape of the early 2000s to the quiet revolution of the five-year plans to my impressions from the summer of 2025.

Now comes the uncomfortable question: what does all of this mean for us—for Europe, for Germany, for our industry, and for our personal and professional future?

I don't want to answer this question with a raised finger. There are enough people who do that. Instead, I want to let the facts speak for themselves and offer a few thoughts.

The Chinese success factors

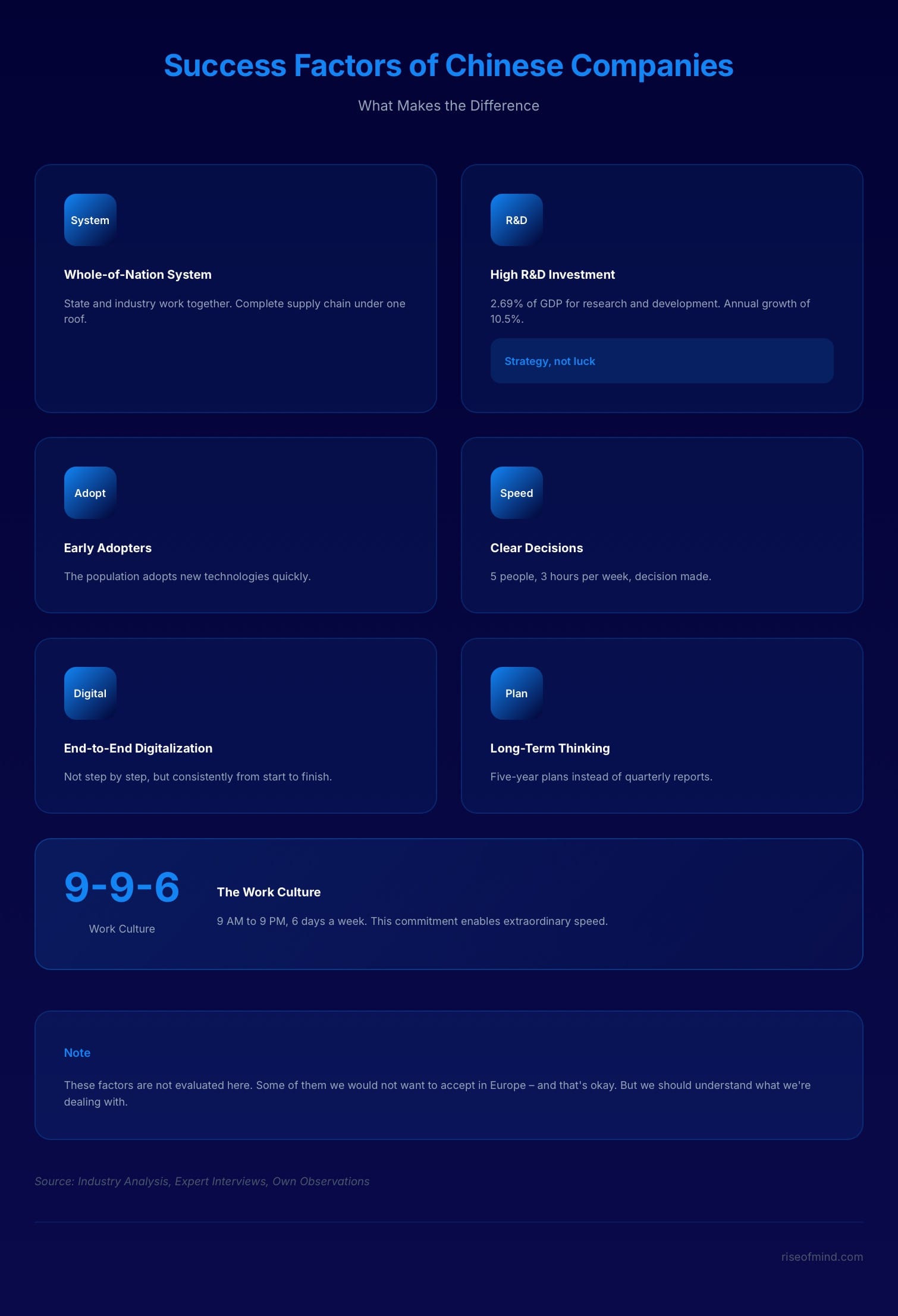

When I try to understand why China has come so far in such a short time, a few factors stand out:

The ‘Whole of Nation System’: In China, the state and industry work together. They control the entire supply chain – from raw materials to the end product. There is no friction between political vision and economic implementation.

High R&D investment: The research and development ratio rose to 2.69 per cent of GDP, with expenditure growing by an average of 10.5 per cent annually. This is no coincidence, but strategy.

A population of early adopters: Chinese people are quick to embrace new technologies. Mobile payments, electric cars, autonomous driving – what has been discussed in the West for years has long been part of everyday life in China.

Clear and very fast decision-making: A small committee of selected experts from a company meets once or twice a week for a few hours and makes decisions. No endless discussions, no voting loops. Everyone else consistently implements these decisions.

End-to-end digitalisation: Digitalisation is not introduced gradually, but implemented consistently from start to finish. The courage to undergo complete transformation is the key.

The 9-9-6 work culture: Working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week – that's almost twice as many working hours as in the West. This enormous commitment enables extraordinary speed and steep learning curves. However, I hear that this model is increasingly being viewed critically, especially by younger Chinese people, and that issues such as work-life balance are gaining in importance. Nevertheless, the difference to the Western working world remains considerable.

I am not judging these factors. Some of them we would never want to accept in Europe. But we should understand what we are dealing with.

The different business culture

Something I have heard repeatedly in many conversations is that hardware is copied immediately in China as soon as it becomes successful – and is now often better and significantly cheaper than the original. Today, a genuine USP can only be achieved through software and ecosystems.

The following pattern can be observed from time to time: a Western company takes over a Chinese company, and initially everyone is happy. After a few months, however, the former Chinese owner sets up a new company next door – with identical products and often even the same employees.

I have a Chinese friend who has told me several times: ‘Never JV with a Chinese’. A Western company should consider very carefully whether it is actually in a position to enter into a joint venture with a Chinese partner.

This is not meant to be a condemnation. It is simply a different business culture, with its own rules and values. If you want to be successful there, you have to know these rules. Because you can only win a game if you understand the rules.

How China sees Germany

A 2025 study by GIZ entitled ‘Chinese Perspectives on Germany’ shows that the Chinese elite is taking an increasingly critical view of the Federal Republic.

Technological backwardness: Although Germany still enjoys a high reputation, it is perceived as backward in areas that will be decisive for the future, such as AI, semiconductors, electromobility and digitalisation. Respondents criticise slow implementation processes and an unwillingness to take risks.

Criticism of foreign policy: Respondents criticise a morally charged foreign policy and an increasing loss of reliability. In particular, the former Foreign Secretary’s description of Xi Jinping as a “dictator” in 2023 is widely seen as a diplomatic blunder whose repercussions are still felt today. All the more sobering is the fact that this mistake is now being repeated. Clearly, we are not learning from our mistakes.

Conflict of perception: From the Chinese perspective, the German image of China is one-sided, prejudiced and reduced to human rights or surveillance. Respondents feel hurt by what they perceive as unjust and unfair reporting and miss recognition of achievements such as poverty reduction.

Call for equality: Despite disappointment over Germany's departure, there is still openness to cooperation on areas of mutual interest. However, a clear warning is issued: arrogance, moralising and know-it-all attitudes will get you nowhere in China.

Germany is no longer perceived as the powerful force it was twenty years ago. However, the German government does not seem to have noticed this loss of importance and continues to lecture China – as if it were still a subordinate workbench.

The relationship can be imagined as a conversation between a former mentor and his now more successful student: the mentor continues to try to impart moral lessons, while the student has long since surpassed him technologically and no longer takes his advice seriously.

Tariffs: A sham debate?

In October 2024, the EU imposed countervailing duties on Chinese electric cars – between 7.8 and 35.3 per cent. The idea was to offset state subsidies in China and protect European manufacturers.

The reality is different:

Price reductions instead of declining sales: In order to remain attractive to European buyers despite the tariffs, Chinese manufacturers have massively reduced their prices. The average price of a Chinese electric car is now around £8,000 lower than in the first half of 2023.

Stable import volumes: These price reductions have enabled Chinese car manufacturers to maintain or even increase their sales figures in the EU.

Hybrid models as an alternative strategy: There is a clear trend towards hybrid vehicles. As these are not subject to the specific electric car tariffs, manufacturers are using them as a strategic alternative.

EREV as a loophole: A new class of vehicles is currently coming onto the market that is exempt from tariffs: EREV vehicles with a range of over 1,000 kilometres.

These tariffs can be thought of as a dam that the EU has built to stem the flood of cheap cars. However, Chinese manufacturers have simply increased the pressure – by lowering prices – while at the same time digging new channels – hybrids and EREVs. The water now flows almost unhindered around the obstacle.

‘Reverse Deng’: Europe learning from China?

An interesting idea being discussed among European experts is to reverse the historical Chinese joint venture requirement and apply it to Chinese companies.

Under Deng Xiaoping, China introduced laws in the late 1970s that forced foreign companies to form joint ventures with Chinese partners. The aim was to exchange market access for technological know-how.

As China is now itself a leader in many key technologies, it has largely abolished these restrictions. European experts are now discussing countering China with its own means: making market access for Chinese manufacturers in the EU conditional on entering into joint ventures with European majority control.

The EU Commission does not seem averse to these proposals and is examining whether these ideas can be translated into concrete policy.

India as an alternative?

In view of the dependence on China, politicians in the German economy in particular are recommending that the country orient itself more towards India. But experts are sceptical.

Luisa Kinzius from the consulting firm Sinolytics writes: ‘India is not an alternative to China in key areas in the medium term.’ German industry's critical dependence on China lies in raw materials, industrial manufacturing and key components for future technologies such as solar, wind and electromobility. India will not be competitive in these areas in the foreseeable future.

India's opportunity lies elsewhere – in the digital ecosystem. India is therefore a strategic addition for companies that want to tap into digital markets of the future. But a replacement for China? Not in sight.

China's own challenges

Despite all the admiration for its successes, China faces considerable challenges of its own.

Economic risks: Weak private consumption, the ongoing real estate crisis and high municipal debt – almost 300 per cent of GDP – could jeopardise growth.

Demographic change: By 2035, a third of the population is expected to be over 60 years old. China is facing a massive shortage of skilled workers. Experts draw parallels with Japan in the 1990s – a state-driven rise that culminated in a property bubble and a shrinking population.

Expectations for 2026: Official media predict a decline in car sales of around 40 per cent in the first quarter and at least 10 per cent for the year as a whole.

Strategic realignment: The focus is shifting in the new five-year plan. Away from mobility, towards quantum technology, bio-manufacturing and the military. Electric vehicles are considered established. A significant market shake-up is expected.

China is not the paradise it is sometimes portrayed as. But the challenges facing the country do not change the facts I have described in this series.

Possible future scenarios for Europe's car industry

What might the future look like? I see five possible scenarios:

What we can learn from China

Long-term thinking: While we think in terms of quarterly reports and legislative periods, China plans for decades. This is a structural advantage that we cannot simply copy – but we can ask ourselves how we can bring more long-term thinking into our decisions.

Speed of implementation: In China, decisions are made and implemented. In Europe, there is discussion, voting, reconsideration and revision. Sometimes speed is more important than perfection.

Openness to technology: The Chinese population embraces new technologies instead of fearing them. This openness is a cultural factor that is difficult to transfer – but we can try to question our own fears.

Integration instead of fragmentation: In China, the state, industry and research work together. In Europe, we have 27 member states with different interests. More integration would be helpful.

Humility and hope

Humility in the face of China's successes is called for. Its proven achievements are enormous: poverty reduction, environmental protection, security, and the fight against corruption. China is now a serious global player with a long-term strategic mindset. The West would be well advised to behave accordingly.

But humility does not mean resignation. The International Energy Agency (IEA) says: The gap is not insurmountable. About 50 per cent of the cost difference in vehicle manufacturing is due to production efficiency and automation. These are things we can influence.

There are still niches where German quality is in demand. There is still innovative strength in Europe. There are still opportunities – if we seize them.

Closing remarks

When I began this series of articles, my goal was to provide information to the best of my knowledge and belief and to encourage readers to reflect on both their professional and personal lives. Not in a patronising or polemical way, but with the aim of providing as objective and balanced a presentation as possible from my subjective point of view.

What I have in my hands: to pass on information. To encourage reflection. Perhaps to make a small contribution so that we in Europe make the right decisions.

I am very happy to engage in controversial but constructive debate – because we Europeans urgently need solutions. And if one or two topics have not been presented correctly, I am happy to learn.

Summary of the article series

The four parts at a glance

Part 1 – Old China (2004–2020): My first impressions of a country on the move. VW-dominated streets, extreme air pollution, China as the world's workbench. The ‘market access in exchange for technology transfer’ deal – entered into with open eyes.

Part 2 – The silent revolution (2012–2024): How China rose to become a technological power through five-year plans, massive investments and strategic acquisitions. The NEV strategy since the turn of the millennium. Control of rare earths. The move away from Western software.

Part 3 – The new China (summer 2025): My return after a five-year break. Clean cities, a completely changed street scene, DiDi Luxe as a mobility experience. Autonomous driving in everyday life. EREV technology as a recycled Western idea.

Part 4 – Europe at a crossroads: China's success factors, the different business culture, the Chinese view of Germany. Why tariffs don't work. Five future scenarios for the European automotive industry.

The key messages

- China has undergone an unprecedented transformation in twenty years.

- The West has underestimated or ignored this development.

- Long-term strategic thinking beats short-term legislative periods.

- Technological leadership has already changed in many areas.

- Europe urgently needs its own vision – and the willingness to implement it.

A positive outlook

The gap is not insurmountable. There are opportunities if we seize them. Humility in the face of China's successes does not mean resignation – it is the first step towards learning.

China is a partner and competitor to be taken seriously. Cooperation on equal terms is possible – but only if we remain strong ourselves. And to do that, we must act now.

Thank you for reading this series. I look forward to your feedback and a constructive exchange.

Sources Part 4:

- GIZ study ‘Chinese perspectives on Germany’ (2025) ([https://www.giz.de/sites/default/files/media/els-document/2025-11/studienbericht-chinesische-perspektiven-auf-deutschland.pdf] (https://www.giz.de/sites/default/files/media/els-document/2025-11/studienbericht-chinesische-perspektiven-auf-deutschland.pdf))

- EU customs analysis: Reports by Mateis Farcas – The Conference Board (), Wolfgang Hirn (https://www.wolfganghirn.de/)

- IEA Global EV Outlook (https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/executive-summary)

- Sinolytics analysis on India (https://www.faz.net/pro/weltwirtschaft/weltwissen/indien-warum-es-fuer-deutschland-keine-alternative-zu-china-ist -200336283.html)

- Bert Rürup: Analysis of Chinese economic risks (https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/kommentare/kommentar-der-chefoekonom-china-ist-ein-zukunftsmarkt-mit-verfallsdatum/29324376. html)

About the author: The author has been visiting China regularly on business since 2004 and shares his personal observations and insights here.