The new China: Impressions from the summer of 2025

This is the third part of a four-part series on China's remarkable transformation. A personal account from a long-time observer.

Five-year hiatus

Between 2004 and 2020, I usually visited China twice a year. Then came the pandemic, followed by various other crises. For five years, I did not set foot on Chinese soil. In the summer of 2025, the time had finally come again.

I was travelling on business in Shanghai, Beijing, Hangzhou and Suzhou. What I experienced there fundamentally changed my perception of China. Not because I was naive – I had known the country for over twenty years. But because more had apparently changed in those five years than in the fifteen years before.

Arrival in Beijing: A different country

What immediately struck me when I got off the plane in Beijing:

A brand new airport (again). Very clean. No honking. Clean air. Great roads. Lots of very modern buildings with impressive lighting.

It was very different before 2020. It was dirty, the traffic was loud and chaotic, and the pollution regularly caused sore throats – at least for me. So, overall, I gained a very good impression. And I know Beijing to be very different, even if that was five years ago.

Everyone I spoke to during my stay confirmed that this is not just a subjective impression. China has indeed changed significantly over the last five years.

Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou: the same picture

The same picture emerged in Shanghai: very clean, quiet and also very safe. Along the Huangpu River, you can cycle for miles on excellent cycle paths on a rented bike. The city, which I remembered from earlier as hectic and crowded, now presented itself as tidy and well-organised (and still crowded, like all big cities these days).

The same picture in Hangzhou and Suzhou: cleanliness, no honking horns, clean air, excellent roads, modern architecture with impressive lighting.

Hangzhou 2025

My conclusion after this trip: I don't know of any Western city that is as clean and where you feel as safe as in China.

Cameras everywhere – but different than expected

Yes, there are a lot of cameras. You notice that immediately. But – and this may come as a surprise – I didn't find it disturbing. It gives a feeling of security. You can move around almost anywhere at any time without feeling uncomfortable.

I know that this topic is controversially discussed in Western media. But I am only reporting my personal experience on the ground here: the omnipresent surveillance did not make me feel threatened, but rather safe. I cannot say whether this is the case for everyone.

The changed street scene

What impressed me most was the street scene. I still remember my impressions over the years:

Twenty years ago, on my first visit in 2004: Almost only VWs on the road.

Ten years ago, around 2015: In Shanghai, at least 50 per cent of the vehicles were Hyundai and far fewer VW.

Today, around 70 per cent of vehicles are of Chinese origin. Korean models are hardly to be seen anymore, and German vehicles are few and far between. At the same time, the first autonomous vehicles are already appearing on the roads.

The figures confirm this impression. The market share of German OEMs in China has shrunk from 24 per cent to 15 per cent – in just five years. Chinese manufacturers now hold a 70 per cent market share in their own country.

This is not just a statistical shift. It is visible, tangible, unmistakable.

DiDi: Mobility on a different level

One experience I never had in the Western world was using DiDi – the Chinese equivalent of Uber.

You order a vehicle via an app, and even the luxury category is considerably cheaper than any Uber or taxi in the Western world. But the price is not what is remarkable.

When you order a vehicle in the luxury category, it is simply an experience that you won't find in the Western world. As a rule, a black limousine arrives right on time – a Mercedes E-Class or BMW 5 Series in the long version, as is standard in China. The vehicle is so clean that you could eat off the floor. That is really no exaggeration.

The drivers speak good English and have all clearly undergone intensive driver training. All drivers wear a black suit, white gloves and a face mask. The vehicles are thoroughly cleaned after each passenger.

What particularly impressed me was that I used this service several times in different cities. The vehicles were absolutely identical – right down to the water bottle and the scent, which was the same in every vehicle. This is standardisation at a level I have never experienced before.

Of course, I am delighted that only German vehicles are used here. At the same time, I inevitably wondered why this is the case. After all, there are also Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other Western manufacturers offering luxury vehicles. Perhaps it was just a snapshot – but the impression remains.

The digital ecosystem: everything works

Alipay and WeChat (Pay) are the essential apps that everyone in China uses to organise their lives. What is striking is that, compared to the Western world, many things in China work very smoothly.

These are everyday things such as restaurant visits, mobility, payment transactions, reservations, freight transport and much more. You open an app, scan a QR code, and the job is done. No cash, no credit card, no discussion.

211 billion mobile payment transactions were processed in China in 2024. The digital yuan is already being tested in pilot projects, with 120 million wallets opened. China has been the world's largest online retail market for twelve years.

This is not a vision of the future. It is everyday life.

The automotive reality in 2025

During my stay, I also had the opportunity to take a close look at the current situation in the automotive industry.

At Auto Shanghai 2025, VW presented the first electric vehicle developed completely independently of Germany in China for the Chinese market. The figures quoted are remarkable: 40 to 50 per cent lower development costs compared to classic development in Germany. 30 per cent lower manufacturing costs. VW plans to have more than 30 locally developed vehicles by 2030.

Audi has also responded: a new brand has been established in China – ‘AUDI’ written as letters instead of the four rings. The first vehicle under this brand was developed in a joint venture with SAIC and will also be produced there.

Chinese OEMs have the declared goal of developing a vehicle in 9 to 12 months and launching a new model every year – as in the IT industry. This is the new benchmark for Western car manufacturers.

Autonomous driving: the second half has begun

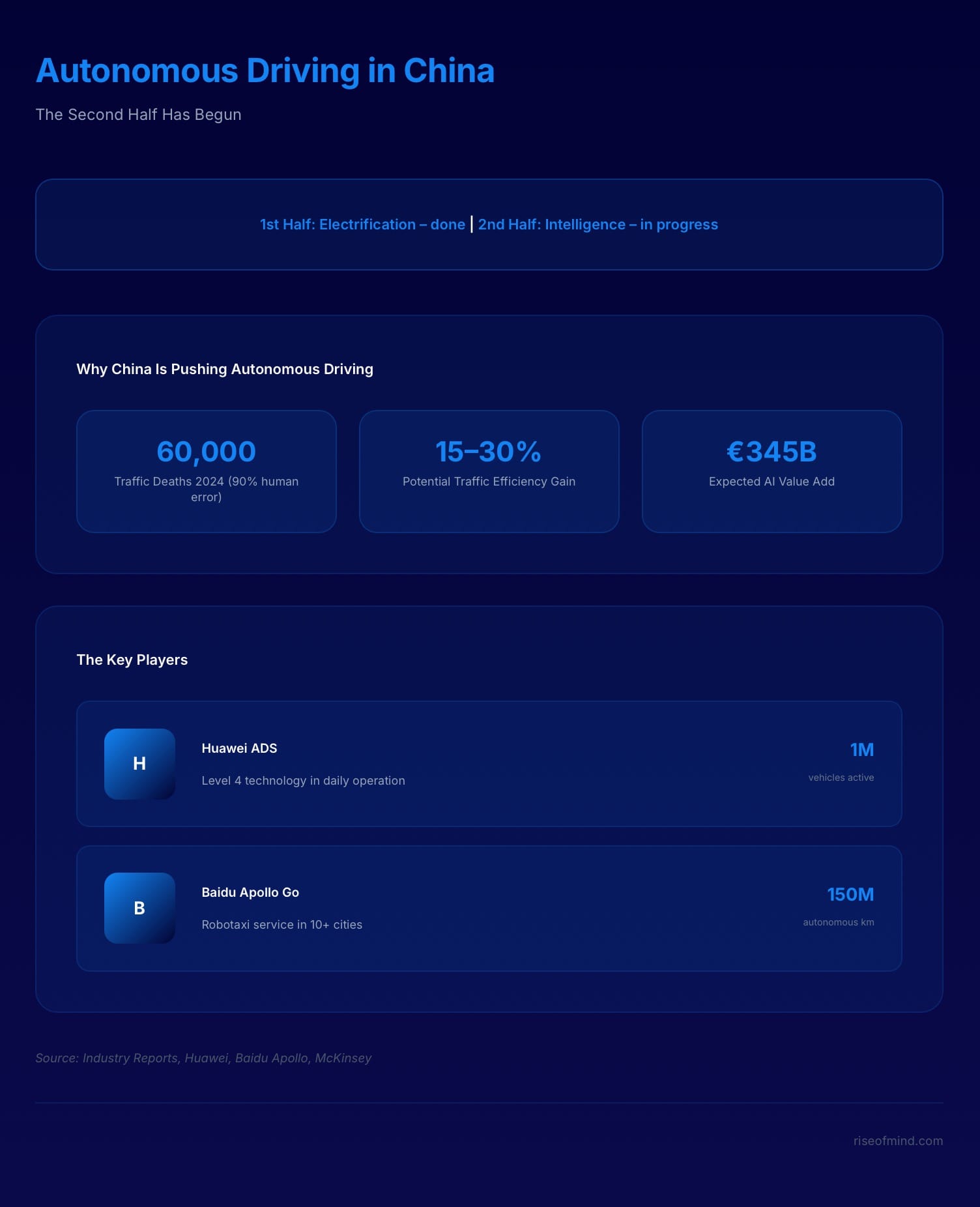

One topic that is being pursued with enormous seriousness in China is autonomous driving. The motivation behind this is not only technological ambition, but also economic necessity.

In 2024, there were 60,000 traffic fatalities in China – 90 per cent of which were caused by human error. The GDP losses due to traffic jams are enormous. Increasing traffic efficiency by 15 to 30 per cent could result in significant economic gains.

The application of AI in the automotive industry is expected to create added value of around €345 billion over the next ten years, with autonomous vehicles accounting for 87 per cent of this. The market volume for connected driving is expected to rise to over €630 billion by 2030.

While Western manufacturers are experimenting with a few test vehicles, Huawei alone already has one million vehicles in everyday use that are technically capable of Level 4 autonomous driving. Baidu Apollo Go, the robot taxi service, is active in over ten cities and has already covered 150 million kilometres autonomously.

Experts say that China has won the first half – electrification. Now it is dominating the second half: intelligence.

EREV: recycled technology

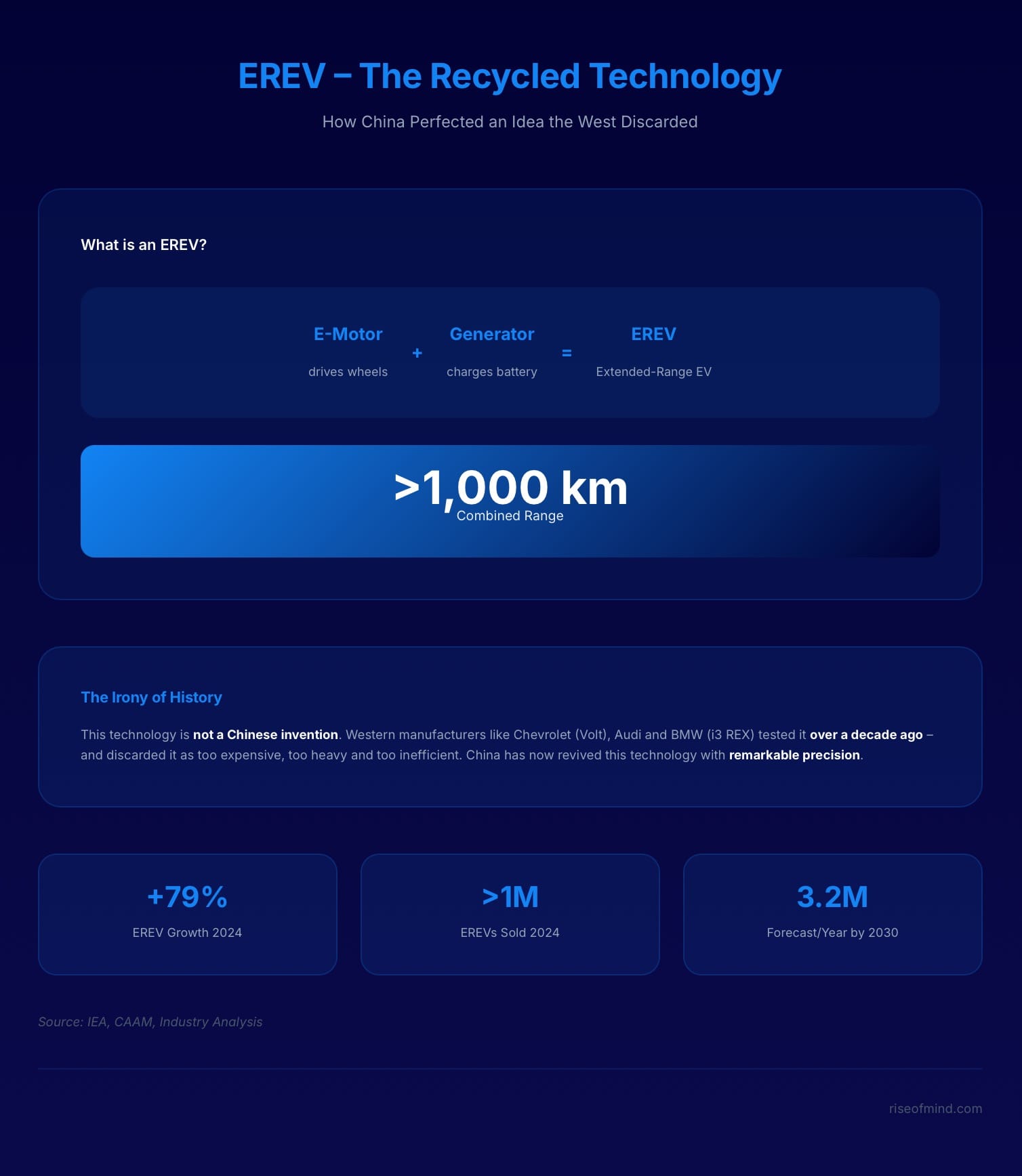

One interesting development I observed during my visit is the so-called EREV – Extended-Range Electric Vehicles. These are electric vehicles with a small petrol generator that charges the battery while driving without directly powering the wheels. This enables combined ranges of over 1,000 kilometres.

The irony is that this technology is not a Chinese invention. Western manufacturers such as Chevrolet, Audi and BMW tested it over a decade ago – and rejected it as too expensive, too heavy and too inefficient.

China has now revived this technology with remarkable precision. In 2024, sales of EREV vehicles in China rose by 79 per cent to over one million units. Experts expect annual production to reach around 3.2 million vehicles by the end of the decade.

While Chinese brands such as Li Auto, BYD and Chery already have series models with enormous ranges on the market, Volkswagen has so far only presented a concept vehicle for the Chinese market.

The EREV can be thought of as a safety net for a high-wire artist: while Europe demands that drivers walk the tightrope immediately without a net – i.e. with purely electric cars – China offers them an invisible net in the form of a petrol generator. This alleviates the fear of falling – the range anxiety – and ensures that many more people dare to walk the tightrope in the first place.

The downside

Despite all the enthusiasm for the visible progress, it should not go unmentioned that China is also currently in the midst of an economic crisis. Unemployment is rising. The official expectation for 2026 is that it will be a difficult year.

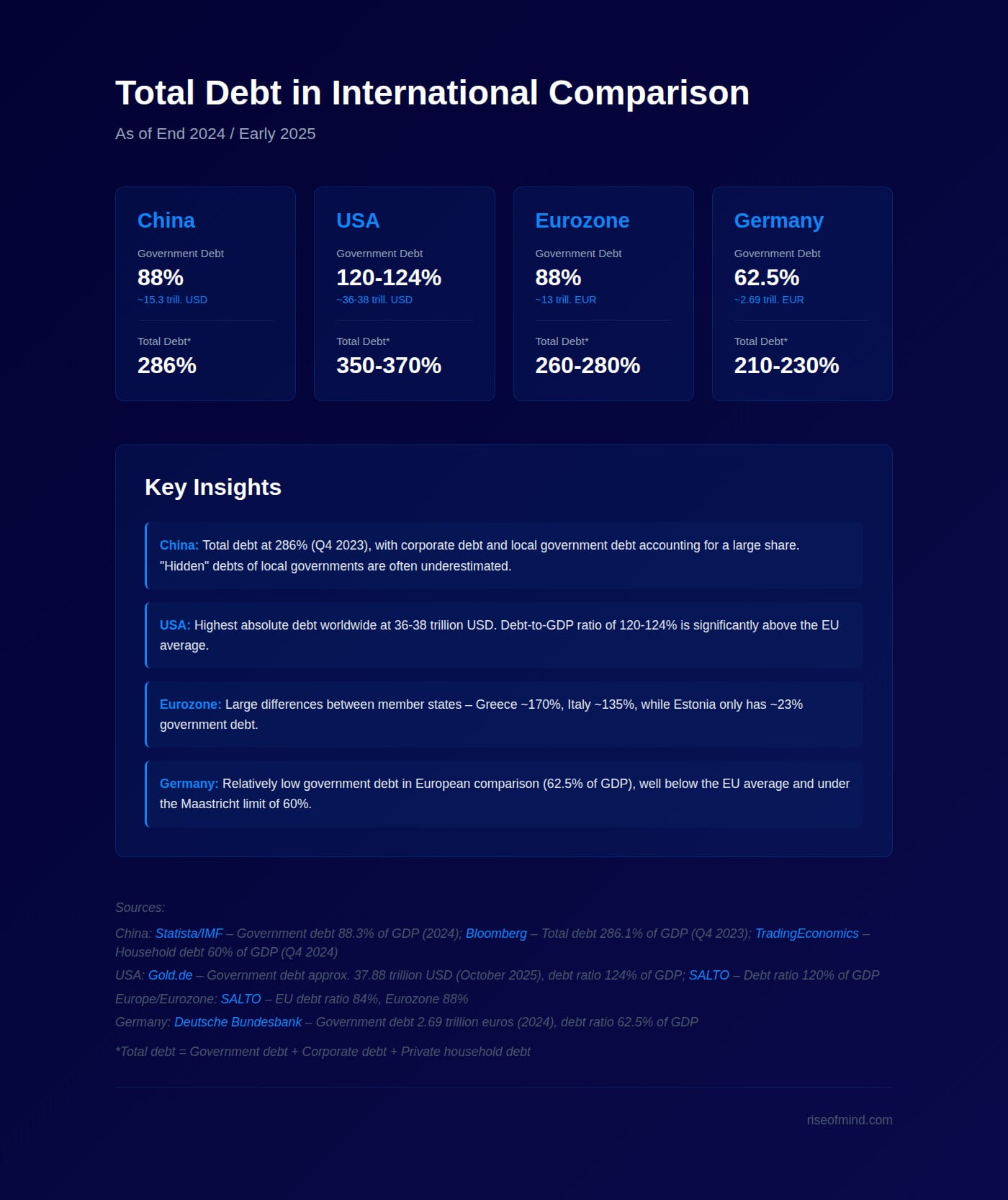

The property bubble is weighing on sentiment. Domestic consumption is weak. Total debt stands at just under 300 per cent of GDP.

China is not the paradise it is sometimes portrayed as. But neither is it the bleak picture often painted by Western media. As is so often the case, the truth lies somewhere in between.

What I take away

After almost two weeks in China, I returned with mixed feelings. Impressed by the visible progress. Pensive about what this means for Europe. And with a certain humility in the face of a development that I had not expected to this extent.

In the fourth and final part of this series, I ask: What does all this mean for us? What options does Europe have? And is there still reason for hope?

The fourth part deals with the consequences: How does China see Germany? Why are tariffs potentially ineffective? What are the future scenarios for European industry? And what can we learn from China's success?

Sources:

- VW China development: Volkswagen Newsroom (https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/de/volkswagen-group-china-5897)

- DiDi descriptions:

Author's own experience

- Autonomous driving: Industry reports, Huawei press releases (https://www.huawei.com/de/deu/magazin/smart-mobility/autonomes-fahren-mit-fun-faktor), Baidu Apollo statistics (https://apollo.baidu.com/)

- EREV development: IEA Global EV Outlook (https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/trends-in-the-electric-car-industry-3), industry analyses

- Market shares: CAAM (https://cnevpost.com/2025/01/13/china-nev-sales-dec-2024-caam/), Statista ()

About the author: The author has been visiting China regularly on business since 2004 and shares his personal observations and insights here.