The silent revolution: China's transformation (2012–2024)

This is the second part of a four-part series on China's remarkable transformation. A personal account from a long-time observer.

The blind spot of the West

In the first part, I recounted my early experiences in China: the VW-dominated streets, the air pollution. China as the world's workbench – loud, chaotic, but profitable for all involved.

What I didn't see at the time – and what the West apparently collectively overlooked – was a strategic transformation that was taking place in parallel with factory production. While we saw cheap labour in Chinese factories, China was systematically building up its own skills. And it did so with a consistency and long-term perspective that is difficult for Western minds to comprehend.

The big difference: five-year plans instead of legislative periods

The fundamental difference between China and the West lies in the time horizon. A German politician must demonstrate success in four years in order to be re-elected. A Chinese strategist plans decades ahead.

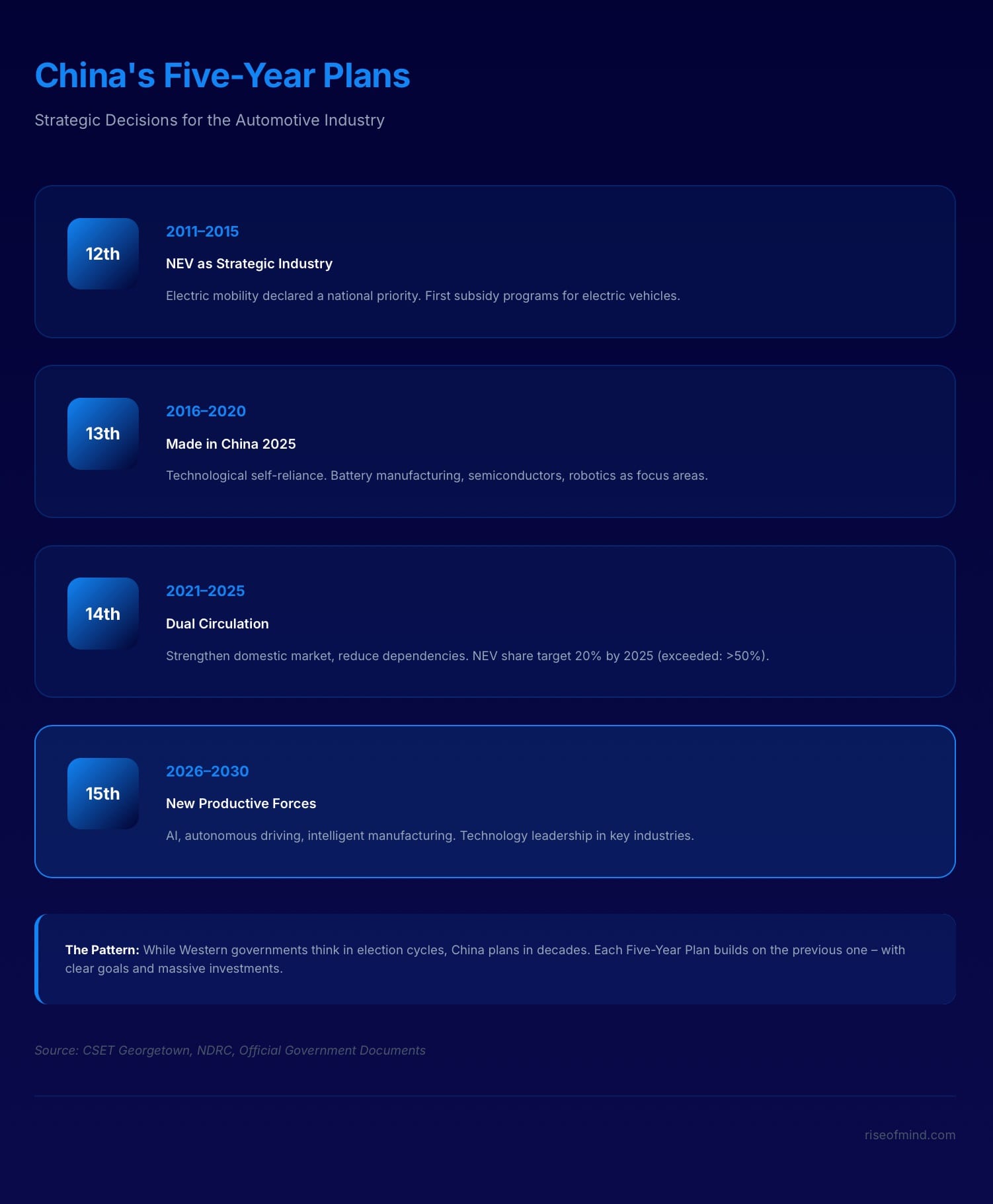

Xi Jinping came to power in 2012 – and is still there today. Every five years, the Chinese government publishes so-called five-year plans, which are then pursued with all possible vigour. These are not non-binding declarations of intent, but binding roadmaps.

A look at the last three plans shows the strategic development:

The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) had the guiding principle of a ‘comprehensively prosperous society’. The focus was on stable economic growth and the expansion of the service sector. Particularly relevant: the ‘Made in China 2025’ initiative was launched and massive purchase subsidies for electric vehicles were introduced. The target of 5 million electric vehicles sold by 2020 was achieved.

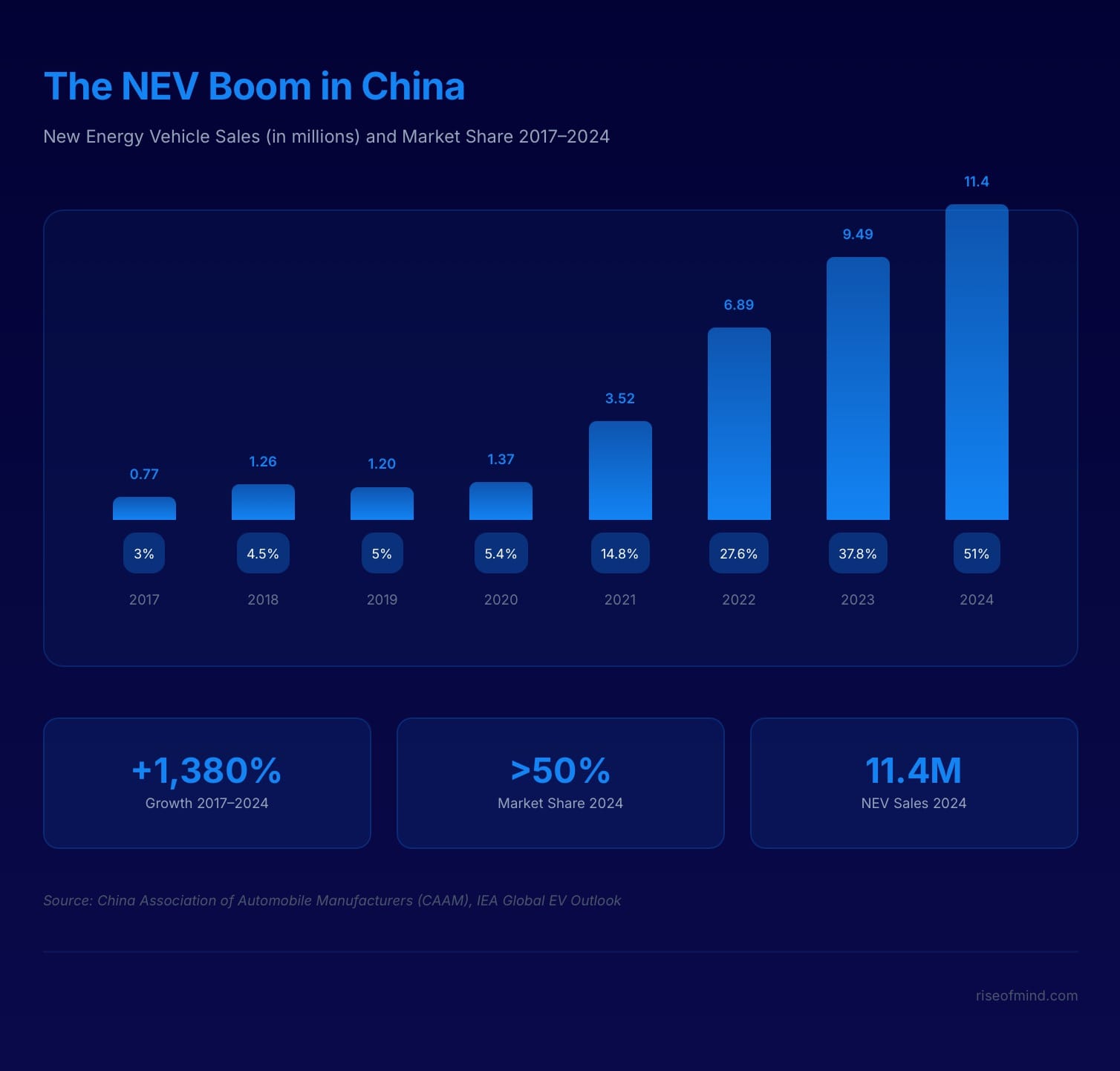

The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) has the guiding principle of ‘high-quality development’. The ‘dual circular economy’ model is intended to reduce dependence on foreign countries. The focus is on technological independence, particularly in chips, operating systems and AI algorithms. Electric vehicles have been established as a key strategic industry, with the goal of achieving a 20 per cent share of new car sales by 2025. This target has been significantly exceeded – by 2024, the share was already over 50 per cent.

The 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030) has the theme ‘New Quality Productive Forces.’ Domestic consumption is to become the main driver of growth. The strategic focus is shifting: quantum technology, 6G, biomanufacturing, nuclear fusion and adaptive robots are now the focus. Electromobility is considered a ‘win’ – the focus is shifting to intelligent manufacturing and complete technological independence.

The automotive strategy: a lesson in long-term thinking

The history of the Chinese automotive industry is perhaps the best example of strategic thinking over decades.

China had no realistic chance of catching up with the established Western and Japanese manufacturers in combustion engine technology. The lead was too great, the technology too complex, the supply chains too entrenched. So a strategic decision was made: the focus was placed very early on the development of ‘NEVs’ – New Energy Vehicles.

Electric mobility was already given intensive consideration in the 10th Five-Year Plan (from 2001) and the 11th Five-Year Plan (from 2006). In other words, China has been working on electric mobility since the turn of the millennium. It is no coincidence that the Chinese automotive industry is where it is today.

Hundreds of billions in subsidies have been invested. Not only in the vehicles themselves, but in the entire ecosystem: battery development, software development, charging infrastructure, securing raw materials.

The figures speak for themselves: between 2017 and 2024, NEV sales in China rose from less than one million to over 11 million vehicles. Market penetration grew in parallel from around 3 per cent to more than 50 per cent.

Systematic technology development through acquisitions

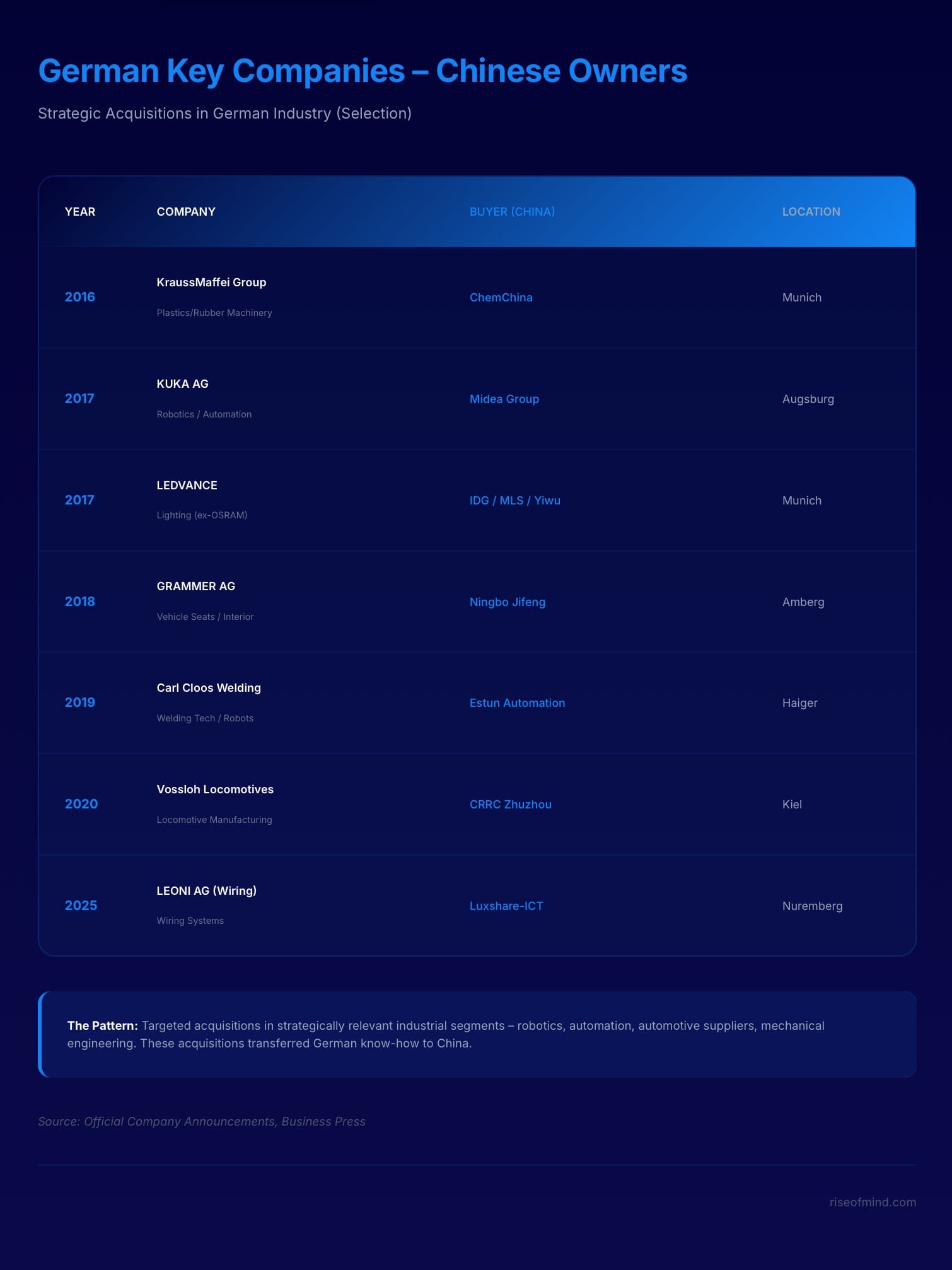

Parallel to internal development, China pursued a consistent acquisition strategy. Chinese companies specifically acquired key German companies – even under the radar of public attention.

An excerpt from a long list:

The list goes on. The pattern is clear: targeted acquisitions in strategically relevant industrial segments – robotics, automation, automotive supply.

The strategic resource: rare earths

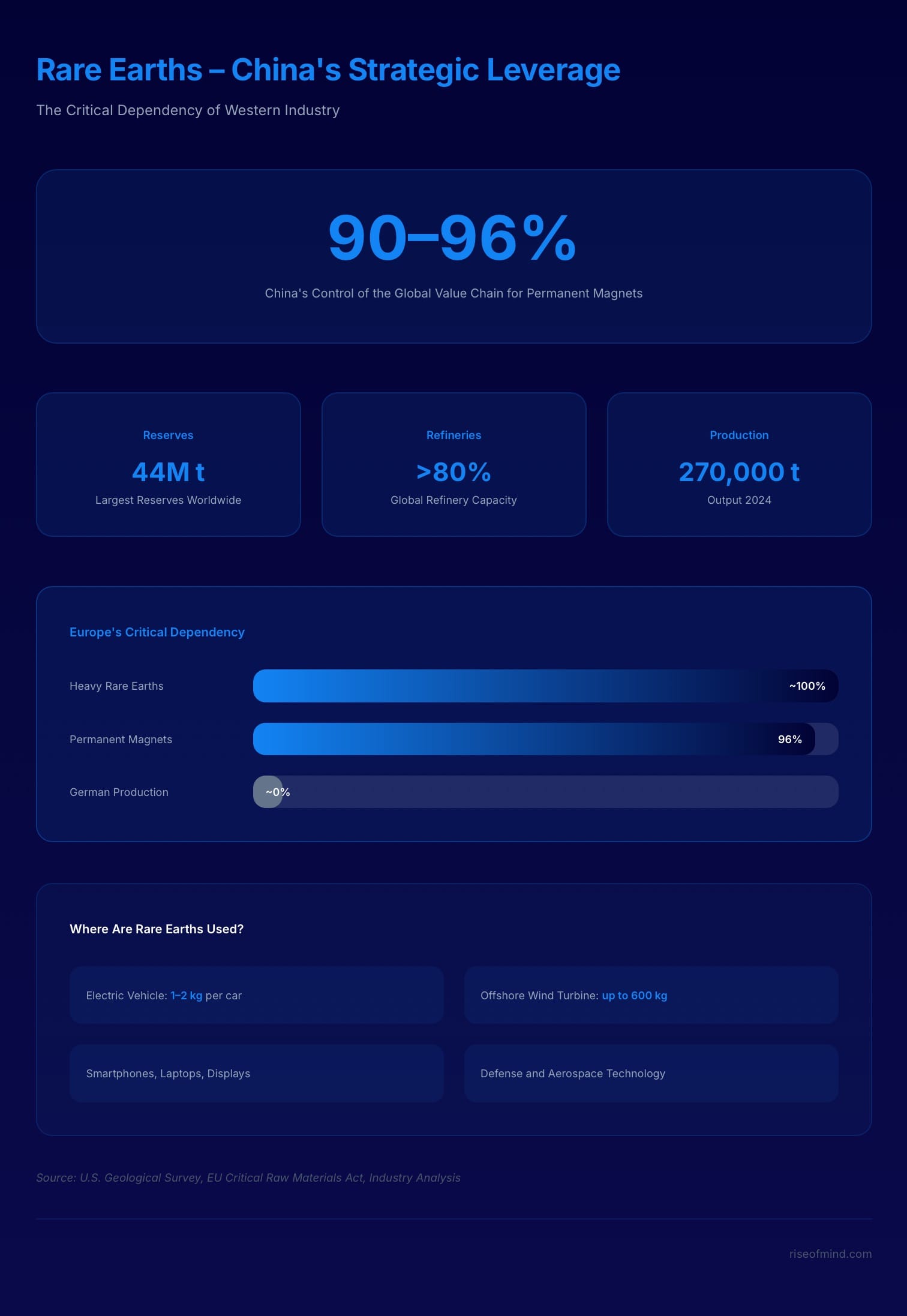

An often overlooked aspect of China's strategy is the early securing of critical raw materials. Rare earths are indispensable for modern technology – from electric motors and wind turbines to smartphones.

The figures are sobering:

- China controls over 90 per cent of the global value chain for permanent magnets, which are indispensable for electric motors.

- Over 80 per cent of the world's rare earth separation and refining capacity is located in China

- With 44 million tonnes, China has the world's largest reserves

European industry is structurally dependent on imports. The EU is almost 100 per cent dependent on imports for heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium. Germany has no significant domestic production or processing capacities.

An average electric vehicle requires 1 to 2 kilograms of rare earth magnets. A single offshore wind turbine requires up to 600 kilograms. The entire green and digital transformation of the West is based on raw materials, the key to which lies almost exclusively in Beijing.

The flight from Windows: technological independence

Another component of China's strategy is the systematic development of independence from Western software. China is gradually moving away from Microsoft.

In addition to Harmony OS – Huawei's operating system with more than a billion installations – there are already several Linux-based alternatives for smartphones, tablets and PCs. Those who want to survive in the Chinese market may no longer be able to do so with Windows software in the future.

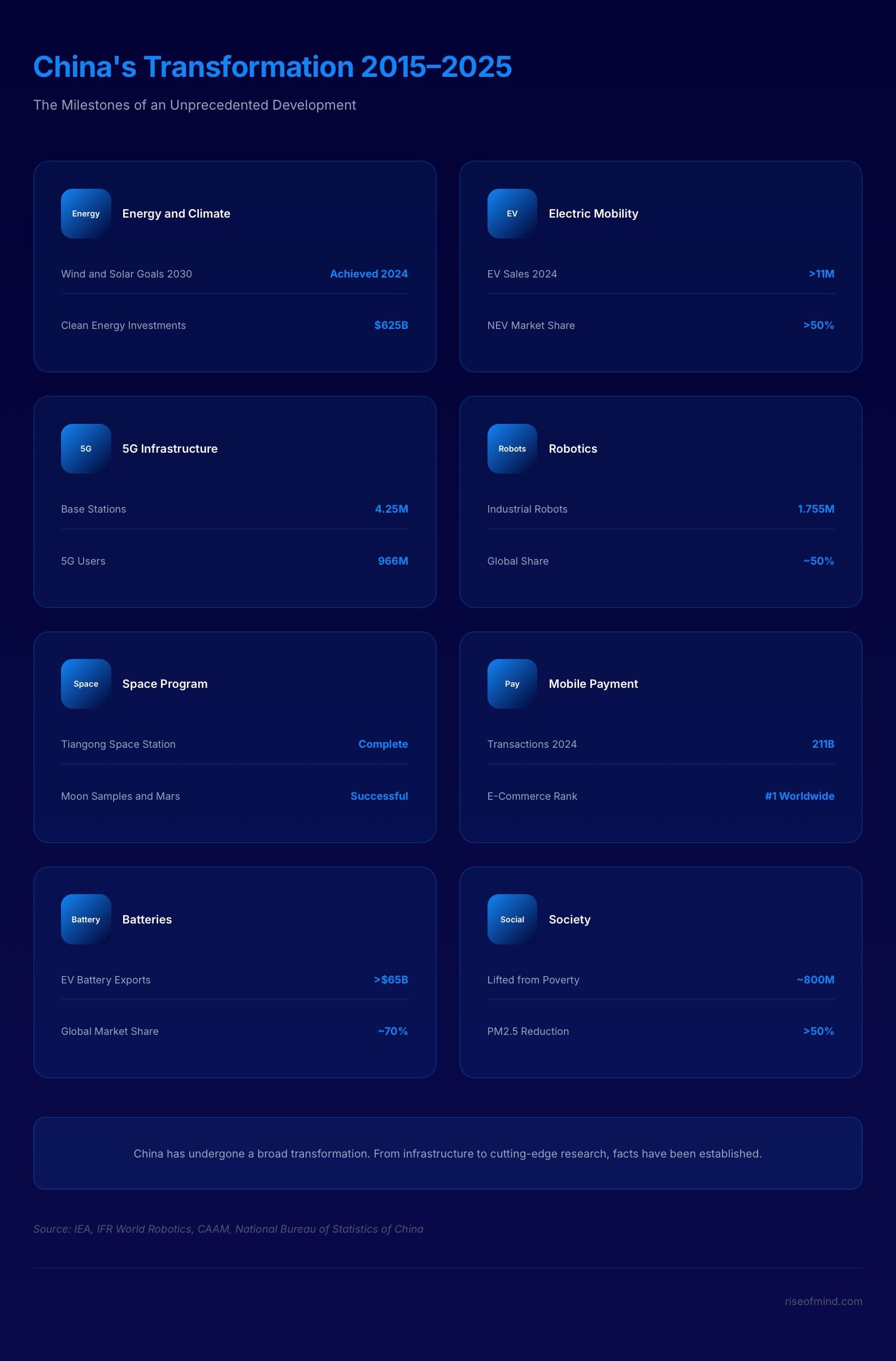

China's transformation in figures

China's transformation between 2015 and 2025 encompasses almost all strategic sectors. Here is a selection of the documented successes:

The difference in thinking

Analyst Dan Wang put it aptly: China is an ‘engineering nation that responds to physical and social problems with a sledgehammer’ – in contrast to the ‘lawyer society of the Western world, which blocks almost everything with a hammer.’

In China, the state and industry work together. They have complete control over the supply chain. Decisions are made and implemented. While the West focused on legalism – imposing tariffs and devising an increasingly sophisticated system of sanctions – China concentrated on building the future.

This is not meant to be an assessment of whether one system is better than the other. But it explains why China has come so far in such a short time.

The new competitive situation

Experts warn that German mechanical engineering and the field of ‘industrial intelligence’ – areas in which German companies have dominated the global market to date – are coming under particular pressure. China no longer wants to simply catch up in new fields, but to take the leading role from the outset: quantum and biotechnology, hydrogen and fusion energy, adaptive robots and brain-computer interfaces, and the next generation of mobile communications, 6G.

While China is planning ahead for the long term and setting strategic frameworks, Europe and Germany are seen as reacting to crises in the short term. They lack a convincing economic vision of their own to meet China on equal terms.

Outlook

When I was last in China in 2020 before the pandemic, I had no idea how much the country would change in the following five years. The transformation I have described here was already in full swing – but its effects only became apparent later.

I returned in the summer of 2025. What I experienced there fundamentally changed my perception of China.

That is what the next part of this series is about.

In the third part, I report on my visit in the summer of 2025: clean cities, a completely changed street scene and a mobility experience that I have never experienced in any Western metropolis.

Sources:

- Five-year plans: Official publications by the Chinese government (https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/china-14th-five-year-plan/), analysed in various economic publications (https://www.undp.org/china/publications/issue-brief-chinas-14th-five-year-plan)

- NEV sales figures: China Association of Automobile Manufacturers – CAAM (https://cnevpost.com/2025/01/13/china-nev-sales-dec-2024-caam/)

- Company acquisitions: Official company announcements from the companies mentioned, e.g. KUKA/Midea (https://chinaobservers.eu/after-kuka-germanys-lessons-learned-from-chinese-takeovers/)

- Rare earths: U.S. Geological Survey (https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-rare-earths.pdf), EU Critical Raw Materials Act documentation (https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-rare-earth-elements-dominance-in-global-supply-chains/)

- Harmony OS: Huawei press releases (https://consumer.huawei.com/en/harmonyos/)

- Technological achievements: IEA Global EV Outlook (https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/executive-summary), World Robotics Report – IFR (https://ifr.org/worldrobotics/)

About the author: The author has been visiting China regularly on business since 2004 and shares his personal observations and insights here.