Old China: Memories of Another World (2004–2020)

This is the first part of a four-part series on China's remarkable transformation. A personal account from a long-time observer.

Before we begin

I would like to clarify a few things in advance. What I describe here is my personal perspective – shaped by regular visits to China between 2004 and 2020, a pandemic-related break and a stay in the summer of 2025. My account may be one-sided and is certainly not complete. The subject is simply too big for that.

There are currently enough people pointing fingers and expressing their opinions about politics or industry. I do not wish to take that liberty. My aim is different: to provide information to the best of my knowledge and belief and to encourage people to consciously consider their own professional and personal future.

I would like to see a public discussion that focuses more on our opportunities – and less on the constant emphasis on shortcomings.

I am very happy to engage in controversial debate, but always in a constructive and solution-oriented manner – because we Europeans urgently need viable answers. And if one or two issues are not presented correctly, I am always open to learning more.

The first step in 2004, stepping off the plane

I still remember the moment when I stepped off the plane in Beijing for the first time in 2004. I was immediately struck by the street scene – but in a completely different way than I had expected. Around 80 per cent of the vehicles I saw were made by Volkswagen. VW Santana, known in China as the ‘Magotan’, as far as the eye could see.

What I didn't know at the time was that I was looking at the result of a strategic partnership that went back twenty years. In 1984, VW became the first Western car manufacturer to establish a joint venture with SAIC (Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation). The first Volkswagen Santana rolled off the production line in Anting near Shanghai in April 1983. What was only a moderately successful Passat offshoot in Germany became a legend in China: almost 4 million Santanas were produced by 2013. The vehicle motorised China – and had a lasting impact on VW's reputation in the country.

The deal was clearly defined from the outset: market access in exchange for technology transfer. A 50:50 partnership, entered into with full knowledge of the facts. And the model worked – VW was number one in China for almost 40 years. At times, VW's market share exceeded 40 per cent.

No pleasure trips

For me, trips to China between 2004 and 2020 were no pleasure trips. It was hectic, loud and the poor air quality was omnipresent. I usually flew home with a sore throat because the air pollution was unimaginably high. Compared to the West, the traffic was extremely dense and chaotic.

There was an air quality index from the US Embassy in Beijing that I consulted regularly. It served as a guide to whether it would have been better to stay in the hotel on a particular day – which I never did, however. The US embassy had already begun measuring particulate matter (PM2.5) levels independently in 2008 and publishing them on Twitter, as the official Chinese data was based on larger particles (PM10) and thus painted a much rosier picture.

In November 2010, the US Embassy's Air Quality Index reached a value above 500 for the first time – a level that the system's programmers had actually considered impossible. The automatic description was ‘Crazy Bad’. This caused a diplomatic scandal, and the embassy quickly replaced the term with the more neutral ‘Beyond Index’. But the incident had already made headlines around the world. In January 2013, values of over 755 were even measured – more than 25 times higher than the limit classified as safe by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

I remember that before major government meetings of the party in Beijing, aeroplanes were supposed to ‘wash’ the air by spraying a chemical. Whether this actually worked is debatable – but it shows how seriously the problem was taken.

Incidentally, the US embassies' air quality monitoring programme was discontinued in 2025, so real-time readings are no longer available through official embassy channels.

The world's workbench

At that time, China was the world's workbench. It was a gigantic success story that seemed to benefit everyone: the West received cheap products, while China gained jobs and foreign currency. Almost everything came from China – and to a large extent still does today. China's trade surplus rose to a record $1.2 trillion in 2025. With domestic consumption currently weak and the property sector in deep crisis, the country is increasingly exporting its excess capacity abroad. Germany's trade deficit with China now stands at $25.5 billion.

Western companies earned a lot of money in China thanks to the huge market. In the early years, they also sold genuine innovations and technical know-how that was initially well ahead of the local market. At the same time, the aura of Western quality, reliability and prestige played a central role. Brands stood for progress and trust – a value that often contributed as much to market success as the technology itself.

In recent decades, thousands of Western expats have been sent to China. With them, Western know-how gradually migrated to the country – a fact that was well known in the industry. Many of these expats were former engineers from Western companies who had lost their jobs and subsequently moved to Asia, mainly to Korea and China. A deliberate transfer of technology through the back door, one might say.

What the West overlooked

What the West has obviously completely underestimated or ignored over the years is that China has developed massively in parallel with pure production. While we saw cheap labour in the factories, China systematically built up its own skills.

The crucial difference to Western democracies is that China does not think and act in terms of legislative periods. Its planning is extremely long-term. Xi Jinping came to power in 2012 – and is still there today. Every five years, the government issues so-called five-year plans, which are then pursued with all possible vigour.

This continuity is difficult for us to comprehend. A German politician must demonstrate success in four years in order to be re-elected. A Chinese strategist plans ten, twenty or thirty years ahead.

The car fleet: a graph that says it all

To understand the transformation China has undergone, it is worth taking a look at the car fleet. In 1978, there were around 23 million vehicles in Germany. By 2024, this number will have grown moderately to just under 50 million.

In China? In 1978, the car fleet was practically zero. Only a tiny elite owned a car – statistically, there was one vehicle for every 6 million people. By comparison, at that time there was one car for every 25 inhabitants in Hong Kong and one for every five in Japan.

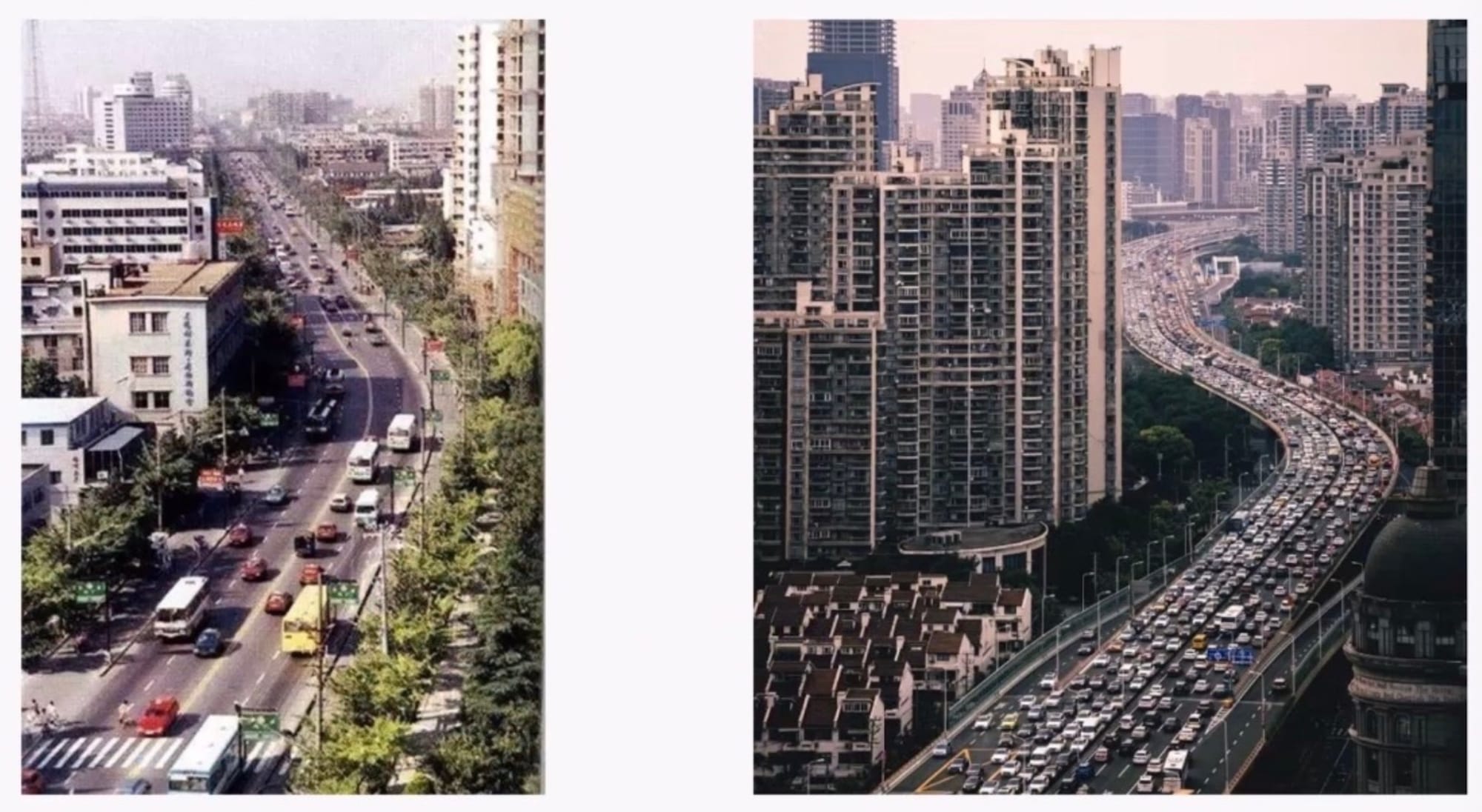

Of course, the consequences of the growing number of vehicles do not fail to materialize:

Today, there are around 193 million cars registered in China. From zero to almost 200 million in less than five decades. That's not just growth – that's an unprecedented transformation.

A different view of the world

One sentence by analyst Dan Wang has stuck with me. He describes China as an ‘engineering nation that responds to physical and social problems with a sledgehammer’ – in contrast to the ‘lawyer society of the Western world, which blocks almost everything with a hammer, for better or for worse.’

While the West focused on legalism – imposing tariffs and devising increasingly sophisticated sanction systems – China concentrated on actively shaping the future: through better cars, more modern cities and more efficient power plants. I don't know if I fully share this view, but the idea certainly has something going for it.

The turning point

Between 2004 and 2020, I usually visited China twice a year. Then came the pandemic and other crises, and the trips came to an abrupt end. A five-year hiatus. When I returned in the summer of 2025, I hardly recognised the country.

But that's what the next part of this series is about.

In the second part, we look at how China quietly planned a technological revolution – and why the West failed to recognise the signs. We take a look at the five-year plans, the electric mobility strategy and the systematic takeover of key Western companies.

Sources:

- VW Santana History: Volkswagen Newsroom (volkswagen-newsroom.com/en/santana-19811984-19710)

- Beijing Air Quality Data: US Department of State Air Quality Monitoring Programme; PMC/NIH study ‘Air Pollution in Major Chinese Cities’ (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5569320/)

- " Crazy Bad‘ incident: ([Science.org, ’Rooftop sensors on U.S. embassies are warning the world about “crazy bad” air pollution"](https://www.science.org/content/article/rooftop-sensors-us-embassies-are-warning-world-about-crazy-bad-air-pollution#656d587e -fb09-4186-b1a8-ede7584f6d95))

- Dan Wang (https://danwang.co)

About the author: The author has been visiting China regularly on business since 2004 and shares his personal observations and insights here.